On September 11, 1916 a hotel worker named Red Eldridge was hired as an assistant elephant trainer by the Sparks World Famous Shows circus. On the evening of September 12 he was killed by an elephant named "Mary" in Kingsport, Tennessee while taking her to a nearby pond to splash and drink. There are several accounts of his death but the most widely accepted version is that he prodded her behind the ear with a hook after she reached down to nibble on a watermelon rind. She went into a rage, snatched Eldridge with her trunk, threw him against a drink stand and deliberately crushed his head with her foot.

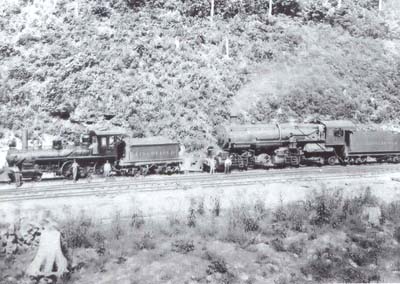

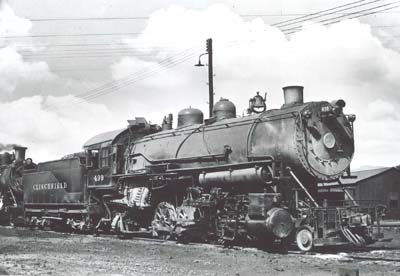

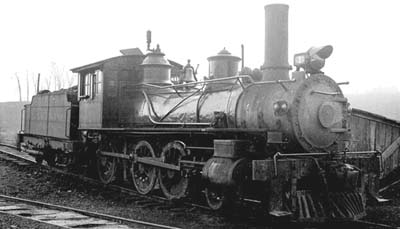

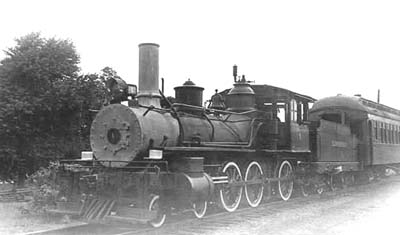

The details of the aftermath are confused in a maze of sensationalistic newspaper stories and folklore. Most accounts indicate she calmed down afterward and didn't charge the onlookers, who began chanting, "Kill the elephant!" Apparently within minutes, a local blacksmith tried to kill Mary, firing more than two dozen rounds with little effect. Newspapers published claims Murderous Mary had killed several workers in the past and noted that she was larger than world famous Jumbo the elephant. Meanwhile, she was impounded by the local sheriff and the leaders of several nearby towns threatened they wouldn't allow the circus to visit if Mary was included. The circus owner, Charlie Sparks, reluctantly decided that the only way to quickly resolve the potentially ruinous situation was to kill the elephant in public. On the following day, a foggy and rainy September 13, 1916, she was transported by rail to Erwin, Tennessee where a crowd of over 2500 people (including most of the town's children) assembled in the Clinchfield railroad yard.

The elephant was hung by the neck from a railcar-mounted industrial crane. The first attempt resulted in a snapped chain, causing Mary to fall and break her hip as dozens of children fled in terror. The severely wounded elephant died during a second attempt and was buried by the tracks.

According to William W. Helton, author of Around Home in Unicoi County, around four o’clock on September 13, 1916, Mary and twelve other elephants were led to the Clinchfield Railroad yard. Mary was the leader of the herd and would not go anywhere without the other elephants following her. After the elephants arrived at the spot where the execution would soon take place, they were led away as one of Mary’s front feet was chained to the railroad tracks. The other elephants became suspicious when they realized Mary was not with them and they began to trumpet warning signals. After a few moments, however, the warnings ceased. It is not known if the elephants were bribed with food or if they stopped trumpeting on their own.

The man who usually operated the derrick was not working that day, so a fireman, Sam Harvey, known to Erwin residents as “One-Eyed Harvey”, was assigned to the hanging. Sam Bondurant, the wreck master, began the execution as soon as the other elephants had disappeared from view. Harvey was instructed to lower the chain, and as soon as the chain was placed around Mary’s neck, Bondurant gave the order to lift her off the ground.

As Harvey began to lift Mary from the tracks, there was a loud ripping noise. They had forgotten to unhook her front foot from the tracks! The ripping sound that some witnesses heard was probably the ligaments which tore in her foot. Unknown to the operators and the onlookers, a link, which made up the chain around the neck of the elephant, had pulled from its welding. As Harvey once again started to lift Mary from the tracks, she began to fight and the swaying motion from the new, rigorous movement caused the link to “jump” from the next link which connected it to the rest of the chain. Mary fell to the tracks and remained dazed until the chain was secured around her neck once more by a brave circus roustabout. People scattered at the sight of the unrestricted murderous elephant. As all the people on the ground ran away, Wade Ambrose noticed from his secure perch on top of a railway car that Mary “jumped to her feet” just as Sam Harvey pulled her up off the tracks for a final time. It took about ten minutes before Murderous Mary was finally dead. Witnesses reported that her body went limp and did not move after she was brought down onto the railroad tracks.

Amazingly, a steam shovel was not used to dig a final resting place for the giant pachyderm. Erwin residents reported that they watched as the circus employees dug a hole with shovels to accommodate Mary’s large size. The circus workers toiled the rest of the day digging Mary’s grave.

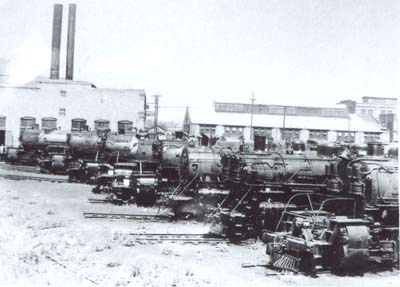

There are rumors that Mary was buried under the place where the courthouse now sits in Erwin. However, she would have had to have been moved almost a mile for this to be true. Witnesses to the execution and burial state that Mary was buried near the roundhouse in the Clinchfield Railroad yard and there isn’t any evidence to prove otherwise.

Sometime during the night, Mary’s large ivory tusks were cut off. Area residents believed that the elephant’s owner had ordered them removed secretly in order to compensate for some of the loss he had taken because of Mary’s early death. He had told reporters that he had paid $10,000 for Mary (the equivalent of $100,000 in 1986, according to William W. Helton).

Why was Big Mary hung? Mary was probably hung to keep Charlie Sparks’ circus from losing admission. Then why didn’t Sparks sell her to another circus? William W. Helton speculates in his book that, because the news of the murder Mary had committed spread so rapidly, Sparks had no other choice than to execute Mary or risk losing admission to his circus. Anyway, Erwin, Tennessee is duly noted in history along with the Clinchfield Railroad as the host site and the industrial muscle necessary for the execution of a murderous elephant.